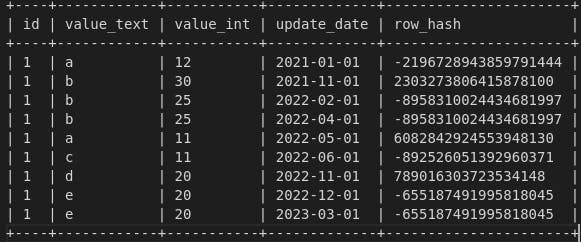

In one of my previous posts, we discussed what temporal tables are and how to join multiple such tables into a single one. In this short practical exercise, we’re going to look at how we can generate a compact temporary table given possible redundant values as input.

Problem statement

Let’s consider an example.

+----+------------+-----------+-------------+

| id | value_text | value_int | update_date |

+----+------------+-----------+-------------+

| 1 | a | 12 | 2021-01-01 |

| 1 | b | 30 | 2021-11-01 |

| 1 | b | 25 | 2022-02-01 |

| 1 | b | 25 | 2022-04-01 |

| 1 | a | 11 | 2022-05-01 |

| 1 | c | 11 | 2022-06-01 |

| 1 | d | 20 | 2022-11-01 |

| 1 | e | 20 | 2022-12-01 |

| 1 | e | 20 | 2023-03-01 |

+----+------------+-----------+-------------+

In our input data, we can see that at our grain (column id ) we’re provided updates on a particular set of dates. But for dates ‘2022–04–01’ and ‘2023–03–01’ the updates are redundant — there is no new information provided.

This can happen, for example, when we extract only a subset of attributes from the data source (where other attributes, which we don’t use, do change).

Now, If we were to transform the above into a temporal table without compacting, we would obtain the following. Notice that, as expected from our input data, two of the periods could be compacted — merged with another adjacent period.

+----+------------+-----------+------------+------------+

| id | value_text | value_int | valid_from | valid_to |

+----+------------+-----------+------------+------------+

| 1 | a | 12 | 2021-01-01 | 2021-10-31 |

| 1 | b | 30 | 2021-11-01 | 2022-01-31 |

| 1 | b | 25 | 2022-02-01 | 2022-03-31 |

| 1 | b | 25 | 2022-04-01 | 2022-04-30 |

| 1 | a | 11 | 2022-05-01 | 2022-05-31 |

| 1 | c | 11 | 2022-06-01 | 2022-10-31 |

| 1 | d | 20 | 2022-11-01 | 2022-11-30 |

| 1 | e | 20 | 2022-12-01 | 2023-02-28 |

| 1 | e | 20 | 2023-03-01 | 9999-01-01 |

+----+------------+-----------+------------+------------+

Compare with the below-compacted version. Notice that two periods 2022–04–01 | 2022–04–30 and 2023–03–01 | 9999–01–01 have been merged with other periods, resulting in a more compact table.

+----+------------+-----------+------------+------------+

| id | value_text | value_int | valid_from | valid_to |

+----+------------+-----------+------------+------------+

| 1 | a | 12 | 2021-01-01 | 2021-10-31 |

| 1 | b | 30 | 2021-11-01 | 2022-03-31 |

| 1 | b | 25 | 2022-04-01 | 2022-04-30 |

| 1 | a | 11 | 2022-05-01 | 2022-05-31 |

| 1 | c | 11 | 2022-06-01 | 2022-10-31 |

| 1 | d | 20 | 2022-11-01 | 2023-02-28 |

| 1 | e | 20 | 2023-03-01 | 9999-01-01 |

+----+------------+-----------+------------+------------+

Note that in both above implementations of the temporal tables the validity period contains both bounds, in other words:

[ valid_from, valid_to ]

Implementation

It’s obvious from the above input that we cannot use DISTINCT or any other de-duplication technique (e.g. with ROW_NUMBER) since these are not duplicates. We’d need a way to look at the attribute values and determine if there is any change (at our grain, in this case by id ).

For this, we’ll use the FARM_FINGERPRINT hashing function, applied to attribute values. Notice the IFNULL wrapper around each attribute, since a NULL value would render the entire hash output NULL as well.

SELECT

id,

value_text,

value_int,

update_date,

FARM_FINGERPRINT(CONCAT(IFNULL(value_text, 'N/A'),

IFNULL(value_int, -1))) AS row_hash

FROM input_datas

This will compute a hash value from our attributes, allowing us to discern between an actual update and a redundant one.

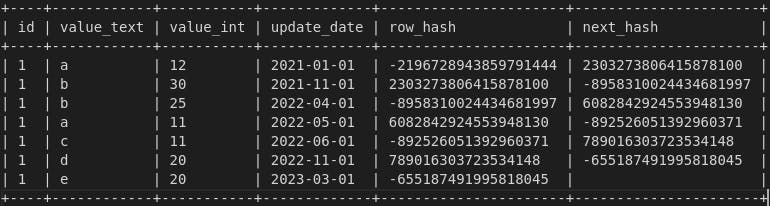

We can now compact the input. We’re going to use a LEAD window function to get, for each row, the value of the next hash (at our grain). Subsequent rows with the same hash values are deemed redundant. We’ll use qualify to exclude the redundant rows.

Notice the IFNULL in the QUALIFY block — this would allow us to keep the last row.

SELECT

id,

value_text,

value_int,

update_date,

row_hash,

LEAD(row_hash,1) OVER (PARTITION BY ID order by update_date) AS next_hash

FROM hashed

QUALIFY row_hash <> IFNULL(next_hash, -1)

This will yield the following data.

We can now generate our temporary table. We’ll start with our update_date as our valid_from, then use the LEAD function the get the next update_date as our valid_to.

Since we’re building a [valid_from, valid_to] implementation, we’ll need to get the value preceding the start of the next period as the end of a period — in our case, subtract a day from the next update_date/valid_form. We’ll also provide a default value for the last known (current) value.

SELECT

id,

value_text,

value_int,

update_date AS valid_from,

IFNULL(DATE_SUB(LEAD(update_date,1) OVER(PARTITION BY id ORDER BY update_date),

INTERVAL 1 DAY),

DATE('9999-01-01')) AS valid_to

FROM compacted

This produces the following output:

+----+------------+-----------+------------+------------+

| id | value_text | value_int | valid_from | valid_to |

+----+------------+-----------+------------+------------+

| 1 | a | 12 | 2021-01-01 | 2021-10-31 |

| 1 | b | 30 | 2021-11-01 | 2022-03-31 |

| 1 | b | 25 | 2022-04-01 | 2022-04-30 |

| 1 | a | 11 | 2022-05-01 | 2022-05-31 |

| 1 | c | 11 | 2022-06-01 | 2022-10-31 |

| 1 | d | 20 | 2022-11-01 | 2023-02-28 |

| 1 | e | 20 | 2023-03-01 | 9999-01-01 |

+----+------------+-----------+------------+------------+

For the full script (including input data), see below.

Conclusion

In today’s practical exercise, we’ve looked at how we can transform possibly-redundant input event data into a compact temporal table.

Thanks for reading and stay tuned for more Data Engineering content.

Found it useful? Subscribe to my Analytics newsletter at notjustsql.com.